Afterlife

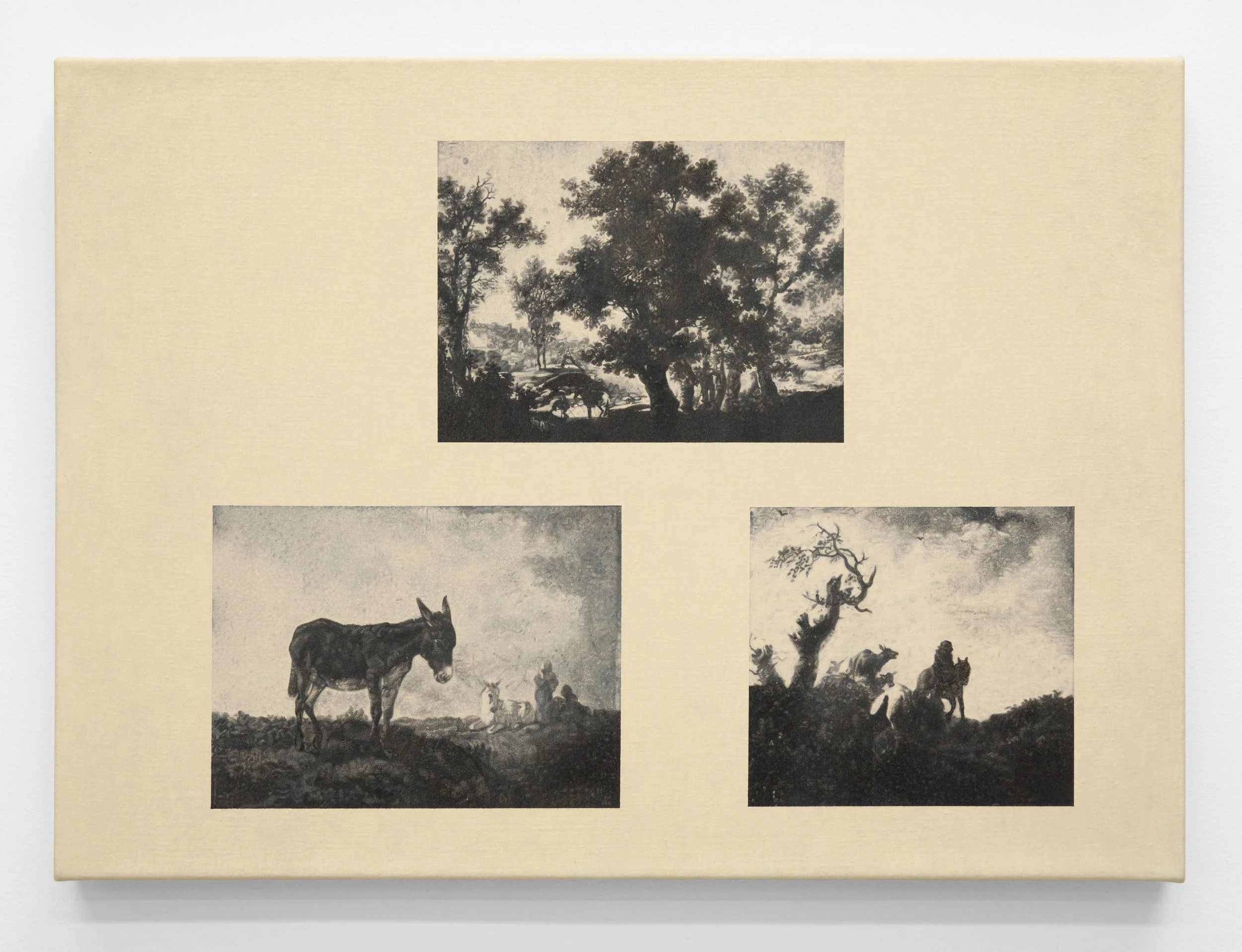

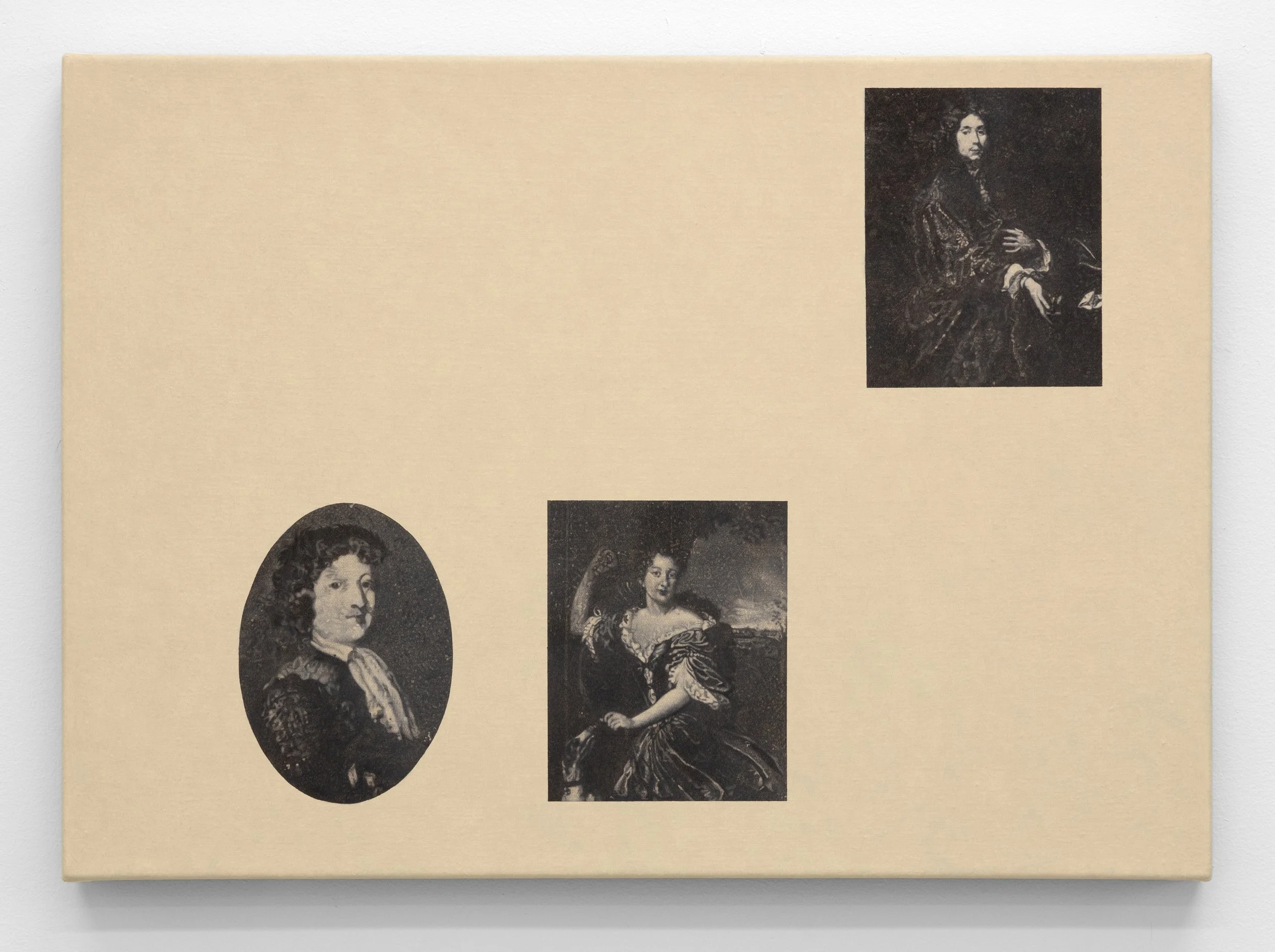

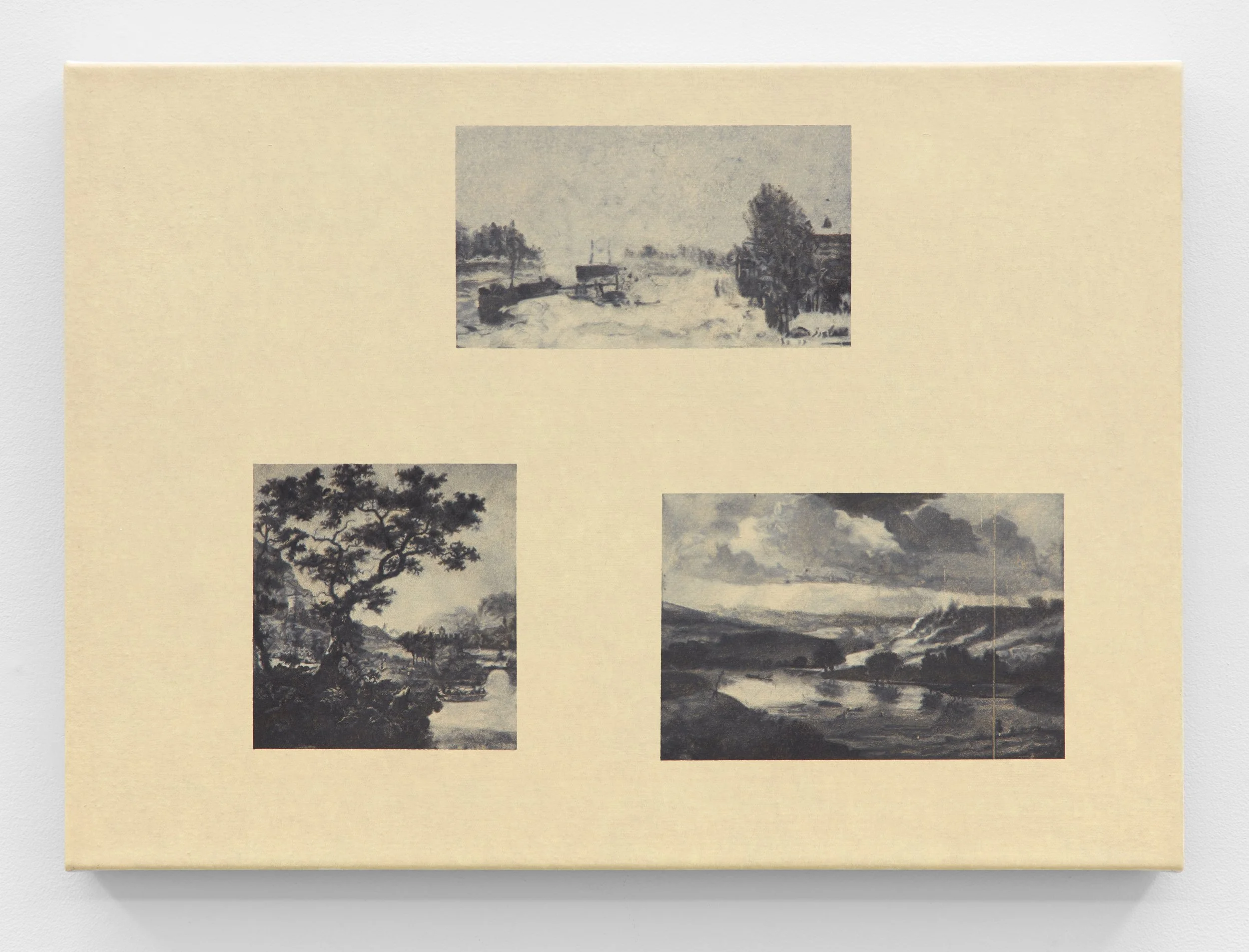

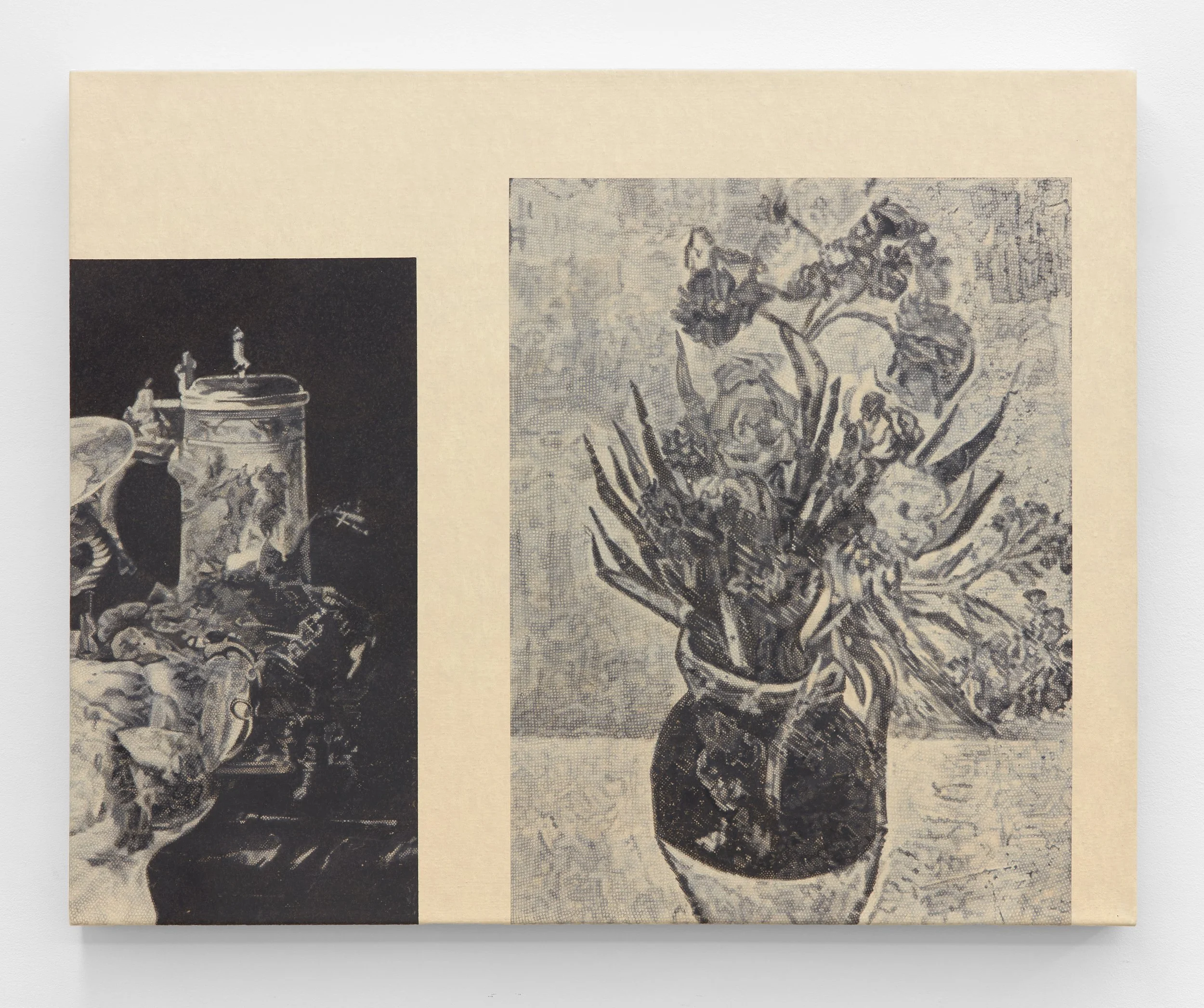

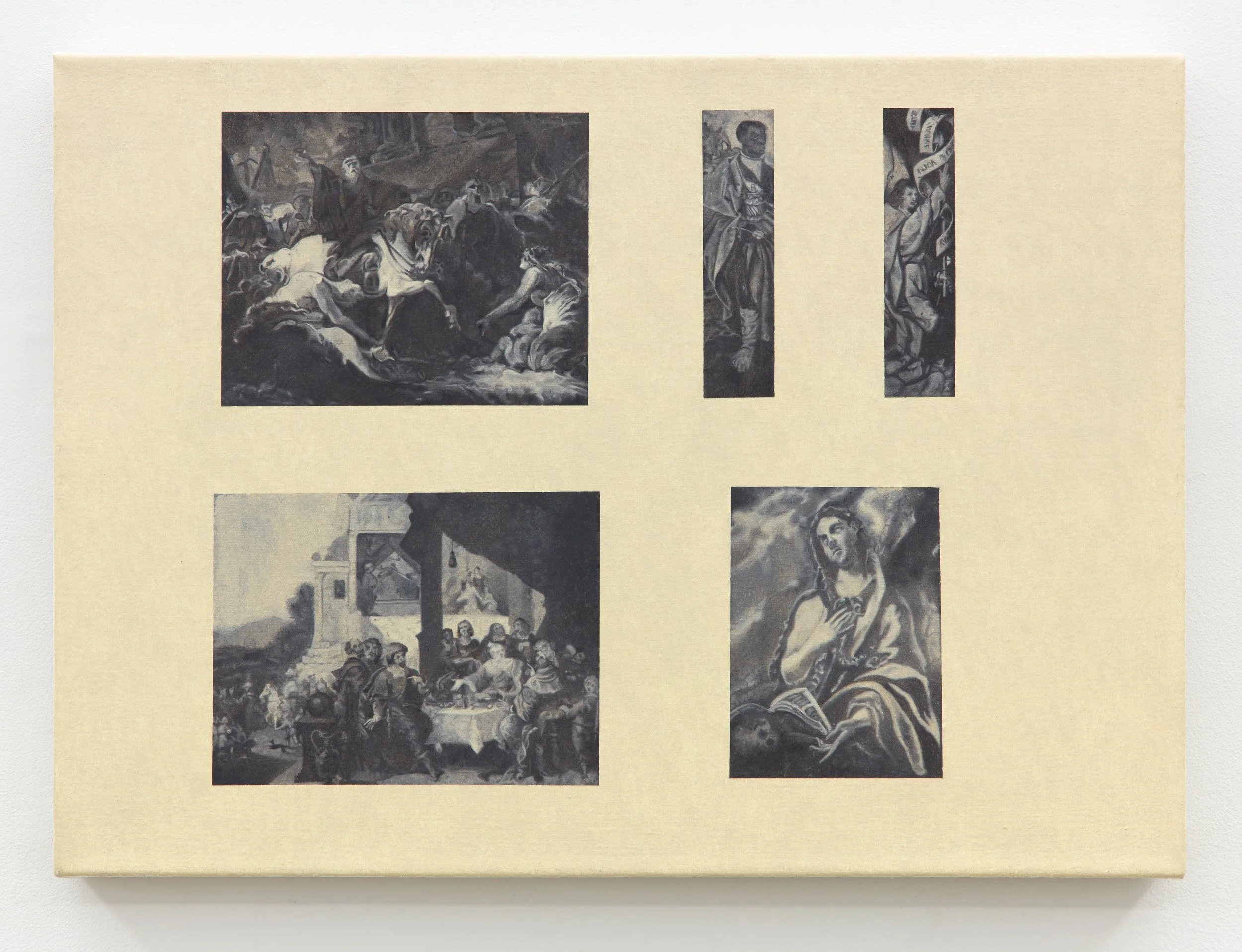

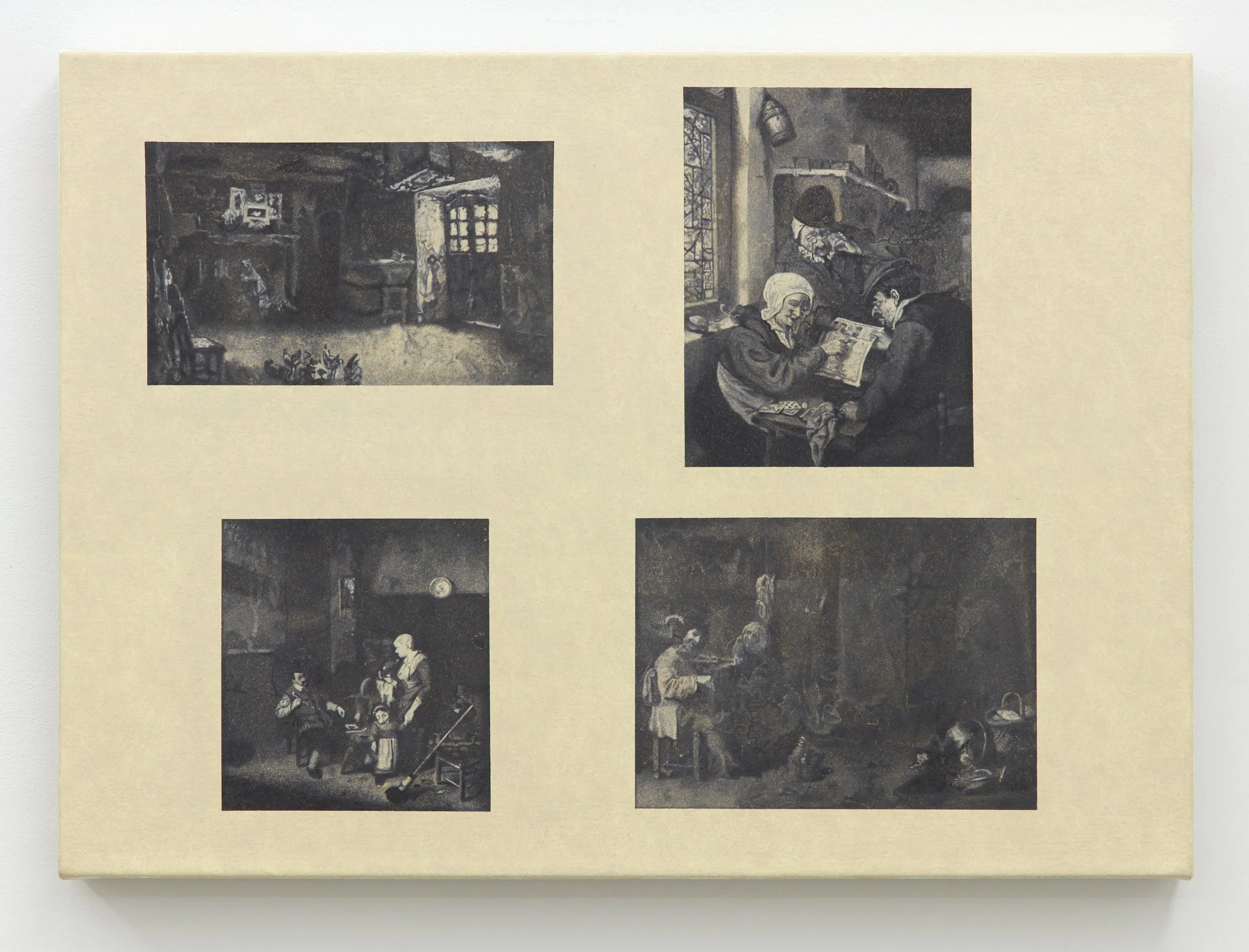

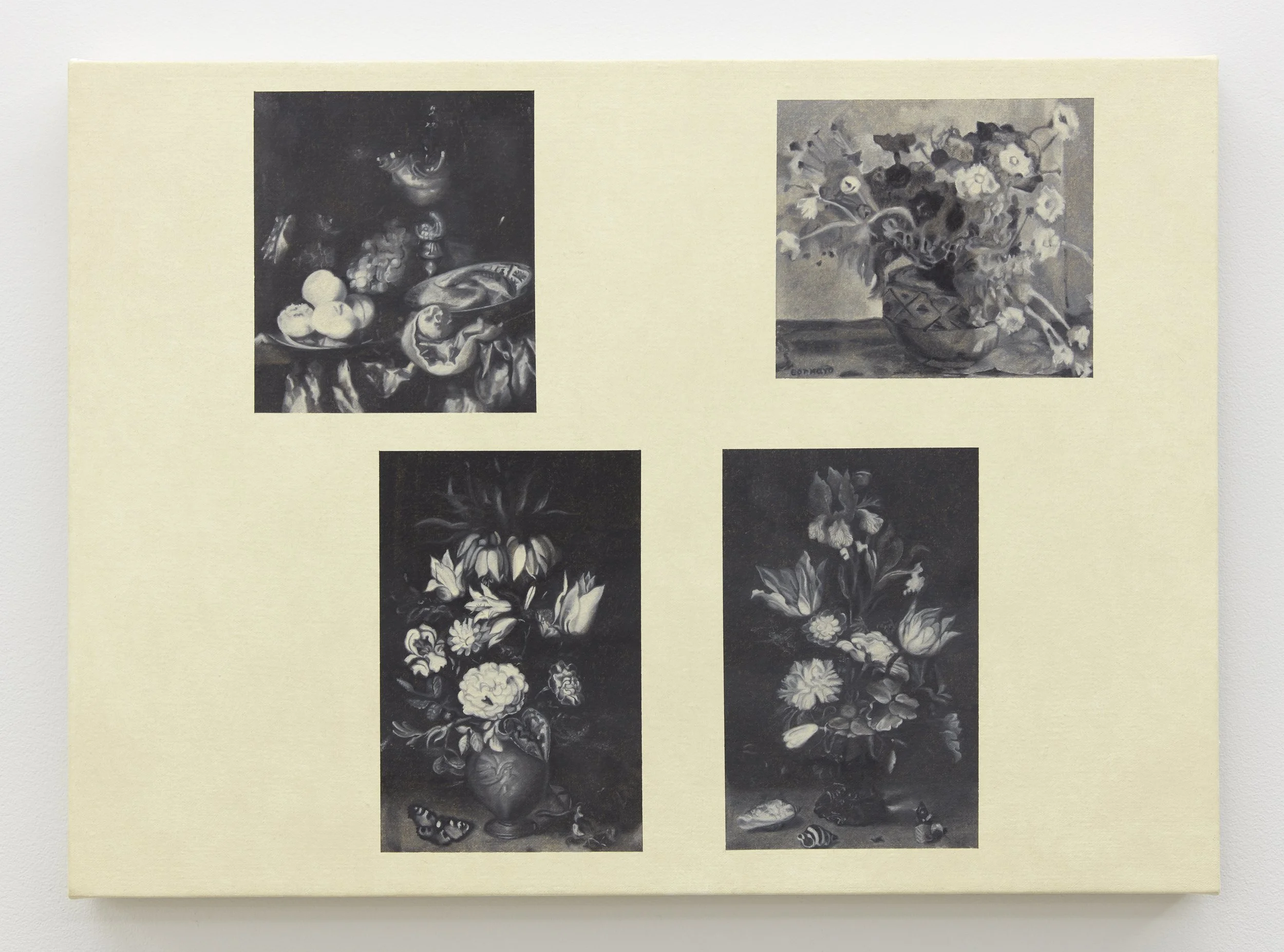

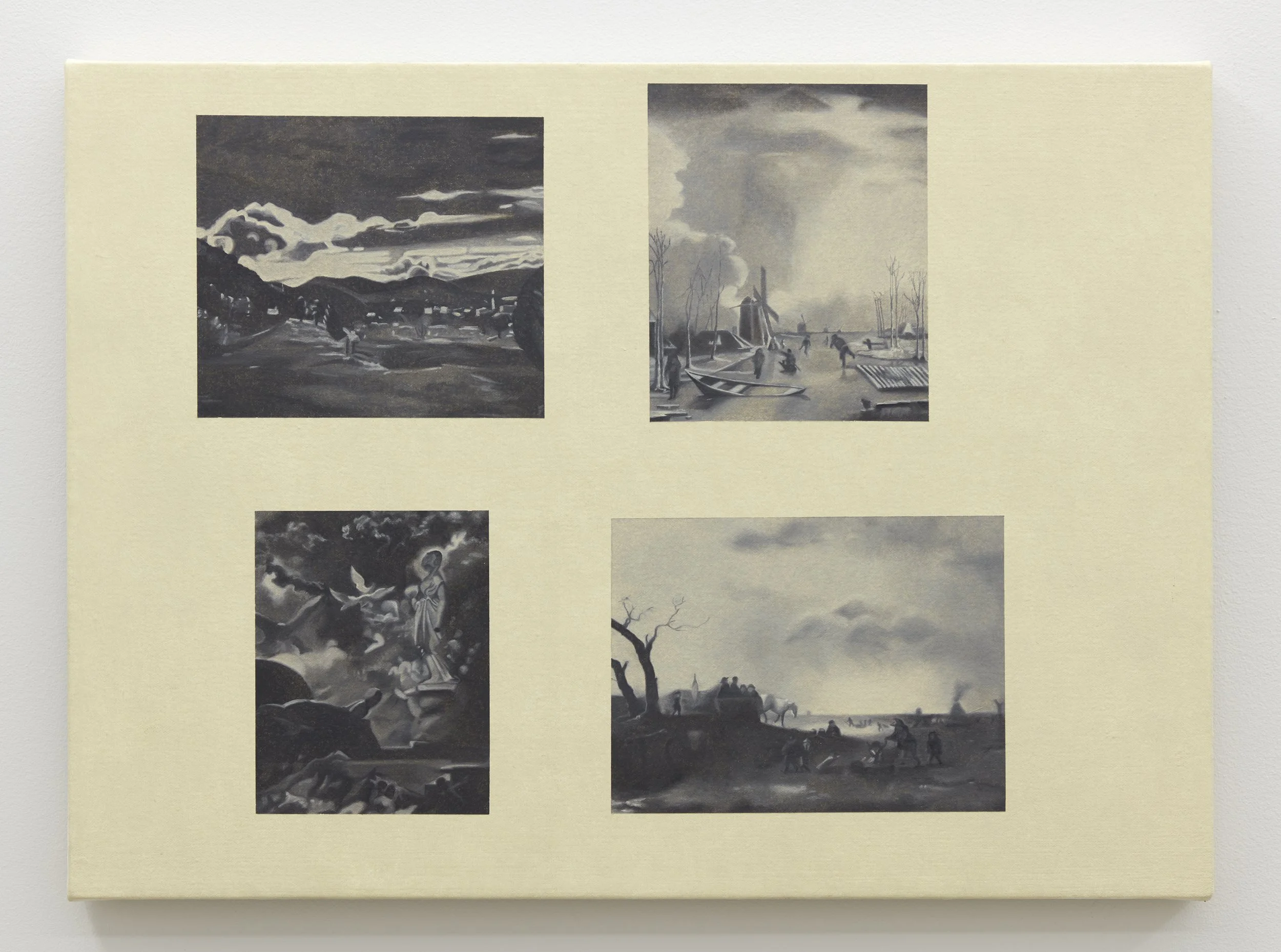

Obsessively observed down to the halftone dot, Afterlife is a series that rematerializes paintings stolen by the Nazis as documented in a 1947 publication by the French Government: Répertoire des biens spoliés en France durant la guerre 1939-1945.

Sherman’s great grandfather’s cousin Justin Thannhauser ran a German gallery of the same name, which held a number of significant shows in Europe including some of the earliest exhibitions of Van Gogh, the first retrospective of Picasso, the first Blue Rider exhibition, and Paul Klee’s first solo show. After the death of his two children, Thannhauser donated his personal collection to the Guggenheim Museum, where it is still on view today. However, during World War II, many artworks were stolen from Thannhauser and never found.

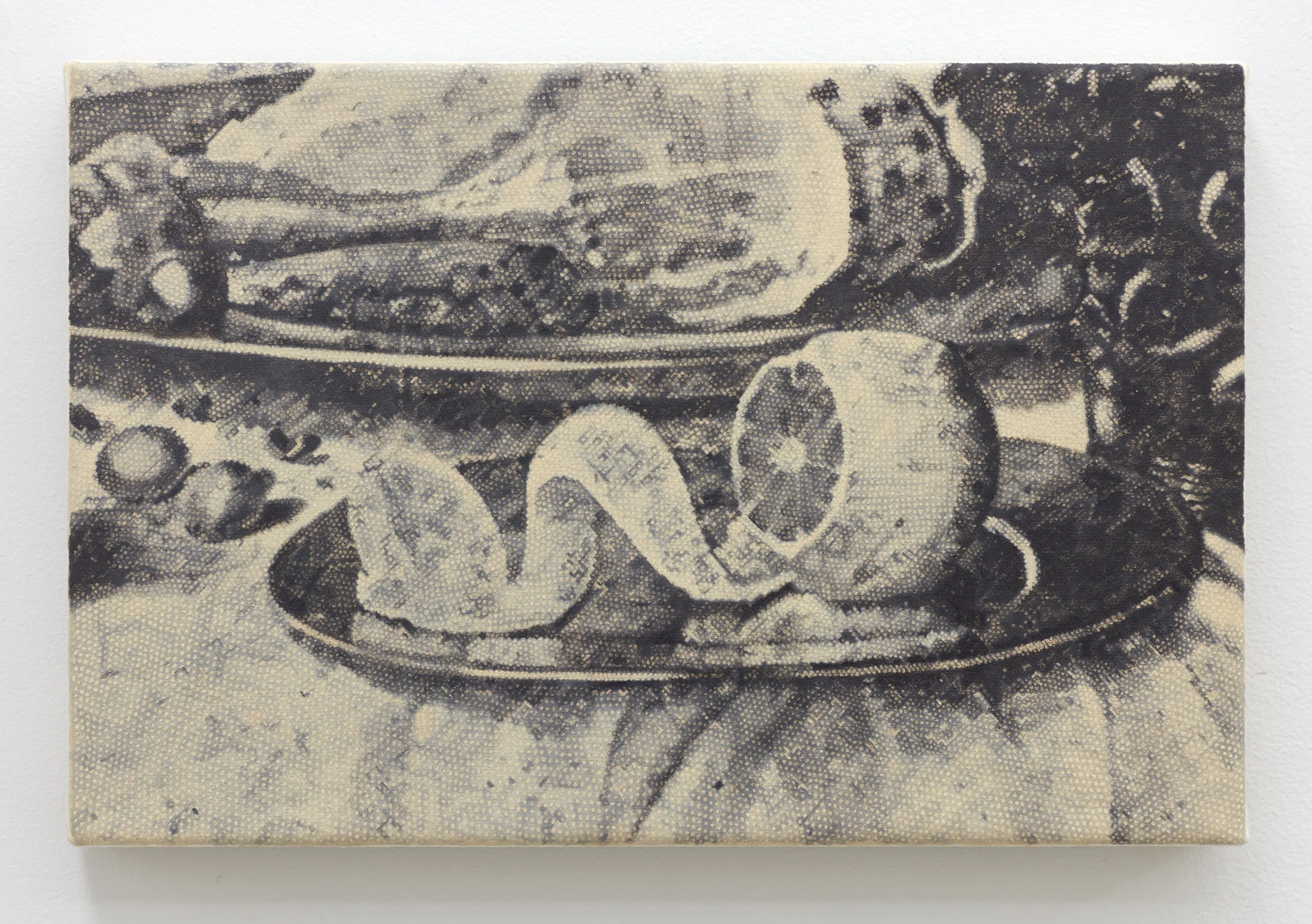

Interested in learning more about these missing works, Sherman ended up locating a photograph of one of them in the 1947 publication. Printed as a tool for the restitution of lost art, the book contains approximately 10,000 claims made by hundreds of families for stolen paintings, a fraction of which include black and white photographs taken prior to the thefts. These photographs are grouped together by genre like specimens in a natural history book. Some paintings in Afterlife replicate individual pages in the publication, while others are scaled so that the paintings they depict are reproduced at original size.

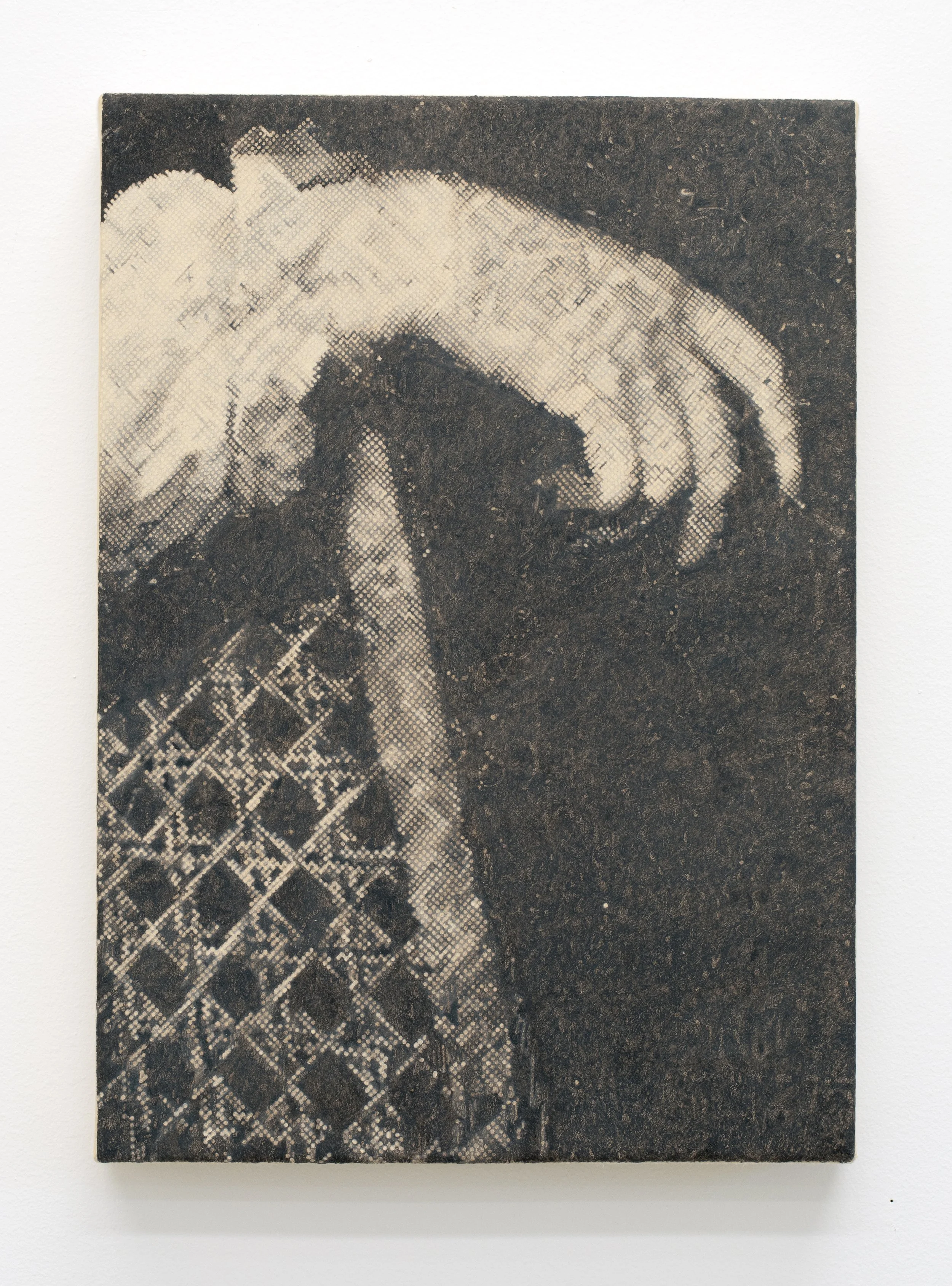

Although the photographs were not intended to be more permanent than their painted subjects, the tragic circumstances of history have rendered them just that. Never being able to fully embody their subjects, the photographs always point to the loss of the original. This is especially apparent in the closeups in Afterlife, where Sherman renders the halftone dot patterns visible. Paradoxically, while these dots define the images, they are also tiny voids—gaps of knowledge impossible to fill in.

These millions of gaps become a stand in for all that has been lost. In the words of Roland Barthes, “Death is the eidos of the photograph.” But, by painting these photographs and thereby reembodying their subjects in oil, Sherman’s paintings offer an unlikely afterlife for the paintings they depict. They may not be whole, but they can breathe again.